November Diary 1

November 3: Paths beckon in sere November, when the bones of things begin to show and the light slants and shortens.

November 5: Frost overnight, roofs and grass sparkling pink at sunrise: a few hours later, a garter snake on the path through Wild Goose Woods, unexpected.

November 8

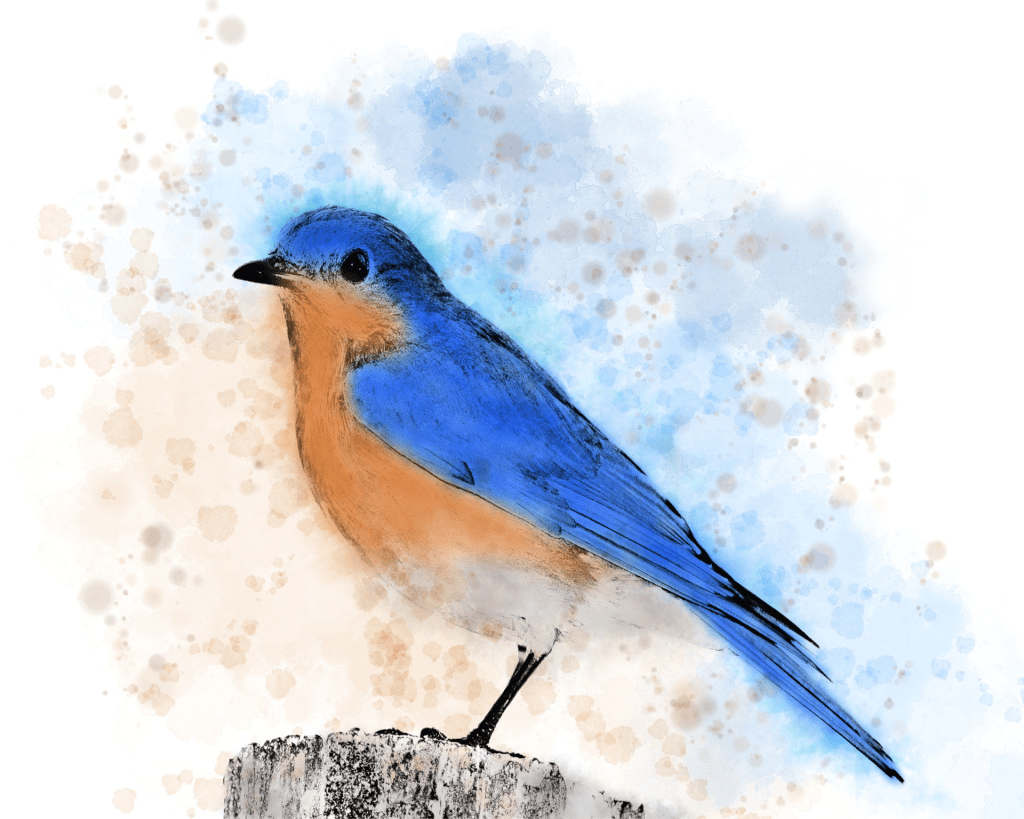

A larch glowed in the fleeting November sun. Close to where I stood, eastern bluebirds flitted from tree to tree, their breasts the colour of autumn oak leaves, their backs and heads refracting the sky, as mercurial as the day.

November 10

Wild Goose pond was still, no ripple of beaver or muskrat or mink, no green heron stalking its edges or mallard leisurely gliding. Above me, the cacophony of a flock of starlings, like a hundred keys turning in rusty locks. Quiet water, loud air.

November 11

The dam on the Speed is out. Among the rocks and debris scattered in the mud of the river channel, mallards feed. One, in flight, drops diagonally to the water, its descending quacks mirroring its trajectory. By the footbridge, a blue heron stands on one leg, head tucked, motionless, prehistoric, more like a shaggy, shedding tree than a bird.

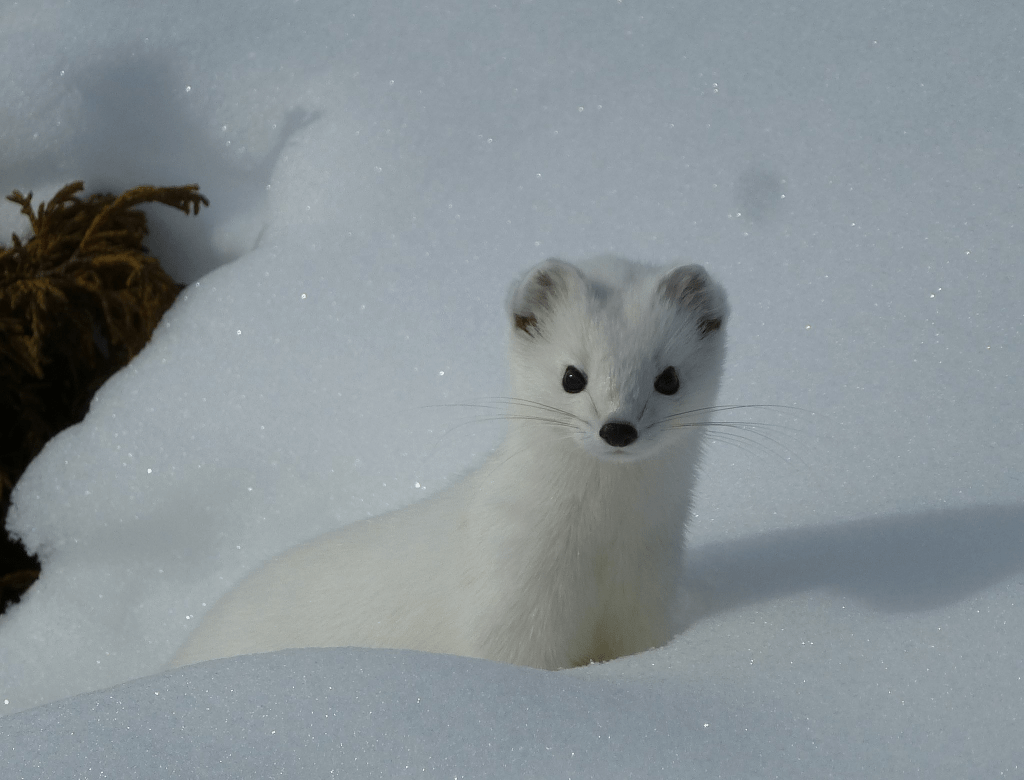

On the wooded east bank path, a red squirrel is a quivering embodiment of frustration, frantic, angry. It circles and chatters, whipping up and down a cedar’s trunk, returning to a hole to thrust its head in. My approach scares it off. I stand, watching. An eye appears, dark, ringed with pale fur. A nose. A head emerges: another red squirrel. It slides out, glances around, slips down the trunk and away. What disagreement, what trespass, did I disturb?