Spring, Rewound

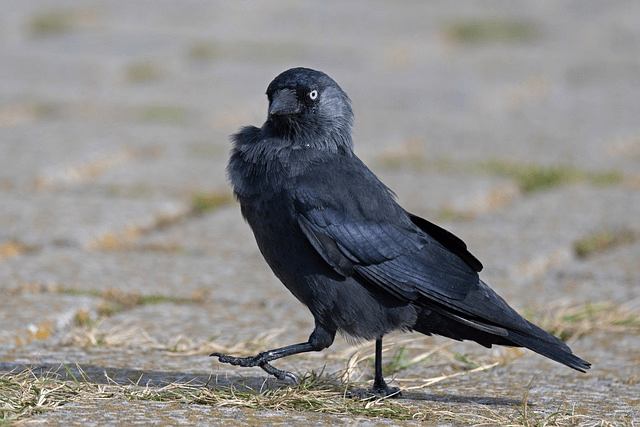

When we left the UK on April 11th spring, at least in Norfolk, was well underway. Birds were claiming territories, wrens and chiffchaffs singing and singing. Jackdaws carried nesting material; med gulls clustered in pairs at Snettisham, and the black-tailed godwits had turned their rich chestnut. Buff-tailed bumblebees foraged among blackthorn and Malus flowers, and the yellow flowers of early spring brightened the ground, coltsfoot and dandelions, primroses and cowslips, and in the wetlands, kingscup.

Eight hours on a plane, London to Toronto, and someone’s hit rewind. Not by a lot, this year: spring is early here. On the 21st, as I write this, the first of the ornamental cherries that line our streets are in flower. But the kingscup – or marsh marigold, as it’s called here – in Wild Goose Woods is still in bud, although I expect it to flower this week.

I heard my first pine warbler this past week, and saw my first myrtle (yellow-rumped) warbler, watched tree and barn swallows dancing over the Grand River and phoebes flycatching from low branches in the maple swamp. Canada geese are hatching goslings, male goldfinches are moulting into summer plumage, and red admiral butterflies – maybe emerging from hibernation, maybe migratory – fluttered along the path we walked Friday, high above the Eramosa River. Bloodroot now stars the forest floor in Victoria Woods.

Twenty years ago, or perhaps thirty, I used to get impatient for spring here; growing up in Essex County, by mid-April spring was much more advanced. Now, looking at e-Bird checklists for Point Pelee, I’m not seeing the same differences. With a couple of exceptions – blue grey gnatcatcher, common yellowthroat – the returning bird species look pretty much the same. But a snapshot is misleading: a quick look back through e-Bird records finds a yellow-rumped warbler reported on the 7th of April.

(Dendroica coronata coronata), by Cephas, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The 7th of April. A yellow-rumped warbler. Some forty years ago or so, we had an Ontario record-early pine warbler – always the first to return – at Long Point on the 6th of April.

I won’t belabour the reasons; we all know them. But I wish I’d never been impatient for spring; I wish my first sight of a yellow-rumped warbler could be one of pure delight, not shadowed by ‘but it’s too early’.

I wish a rewind was possible.