The First Week of Spring

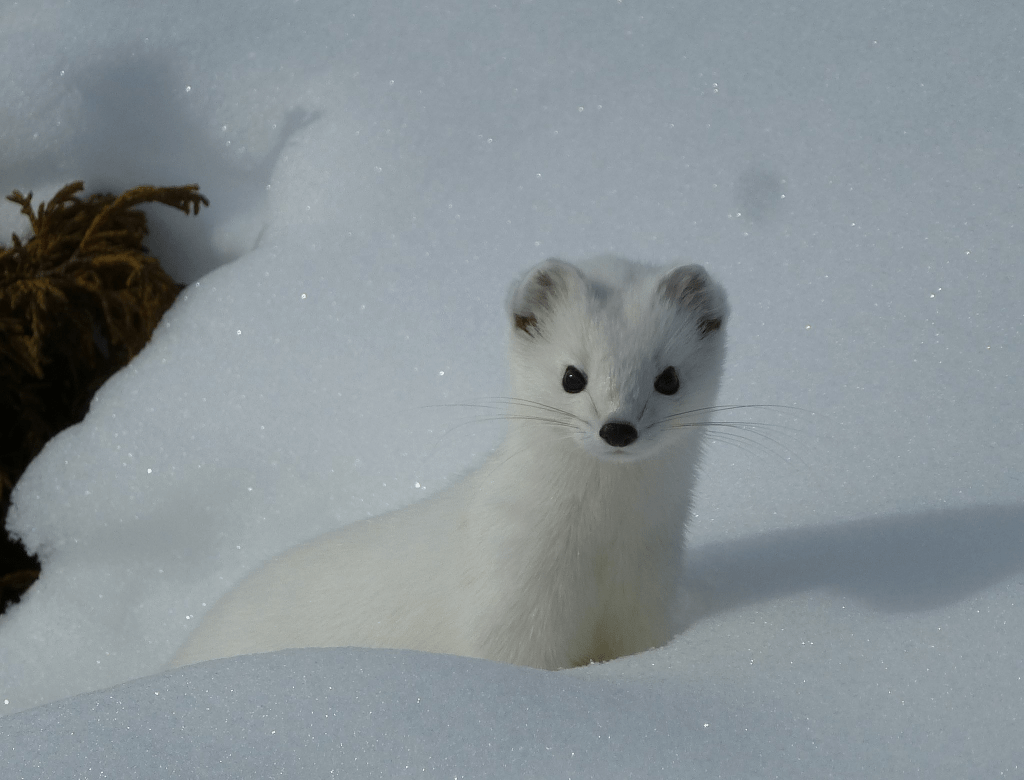

Spring may be here, but it’s dancing with us: one of those dances where it’s one step forward and one back. We’ve had days of sun and relative warmth, and days of sleet and snow flurries and a temperature hovering around freezing. Blue skies and grey, and on the ponds the ice melts a little, then freezes again, then melts a little.

A line of crabapples near one of the village ponds has been discovered by the robins. The winter-cured fruit is a deep purple-red, its sugars concentrated in the desiccated flesh. The robins love it. So do the starlings, whose starred plumage of winter is just beginning to show the iridescence of summer. On the nearby feeders, male goldfinches too are moulting, black and yellow replacing dun.

Where the snow has melted back from the field edges killdeer forage; I hear them before seeing them, their high, onomatopoeic call audible even from inside the car. At the confluence of the two rivers that shape my city, a lone male common merganser is grooming itself, twisting and splashing, ignoring the mallards and Canada geese and ring billed gulls surrounding it. Later a single male bufflehead arrows in.

At the Arboretum there are bluebirds, always an early migrant, one song sparrow—and overhead, three tundra swans, brilliantly white against the blue sky. We’re not on their main flyway here, but every year a few come through; tundras, and more and more trumpeters every year, a reintroduction success.

Outside the city, blue piping festoons stands of maple, and even on urban lawns trees have been tapped. The light lengthens, and in xylem and blood and earth, sap and hormones and the green spears of the first bulbs rise.