November 14: Rural Roads

Five sandhill cranes flew low over Glen Morris road, arising from the corn stubble to my left. Not calling their haunting cry, but still a sight that makes me catch my breath, and reminds me, every time, of the beauty there is in the world.

November 16: University of Guelph Arboretum

The small pond is frozen, surprisingly, a thin skim of ice over its surface. Juncos chip from the reeds surrounding it, flying up, white tail feathers flashing, to the cedars at the side of the lane.

Further along the track a larch is brilliantly gold against the sky and the bare trunks of other trees. Goldfinches, drab in comparison in winter olive, flit among branches; chickadees feed low on the galls on goldenrod stems, the plants’ flowers, once as brilliantly yellow as the larch or as summer goldfinches, now turned to fawn fluff. Milkweed pods are stripped bare.

On the path through Wild Goose Woods, a wood frog hops clumsily away at my footfall, landing badly, struggling to right itself. The air temperature is perhaps 7 degrees C; the frog is cold. I don’t expect to see a wood frog in the middle of November. I’m too surprised to get a picture before it disappears into the underbrush.

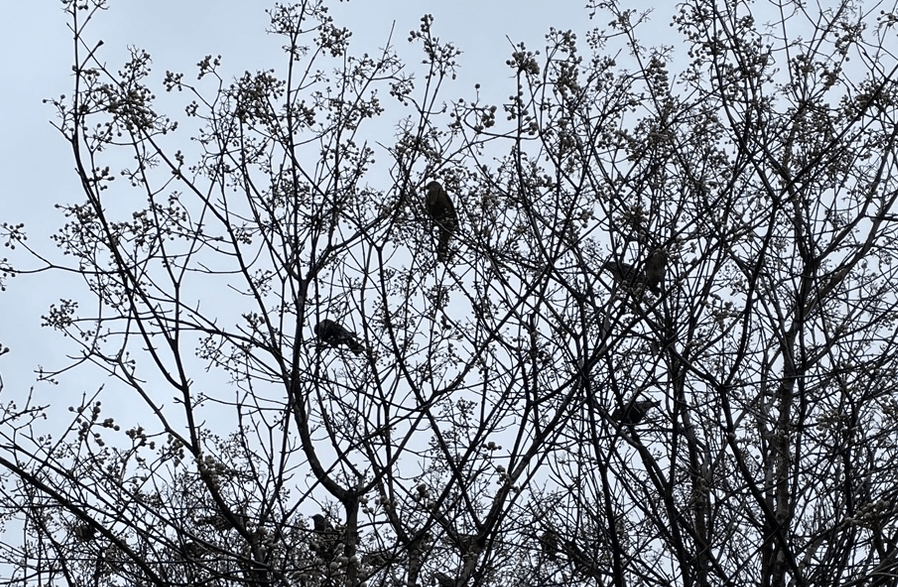

I’m hoping for brown creeper at the maple swamp, but I neither hear nor see one. But a deep ‘gronk’ breaks the silence, repeated three times, then another triplet call, then a third. I can’t see the raven, but it’s there—and the crows know it too, their mobbing call gathering more of their kind to harass the raven. A single unkindness, and suddenly a murder.

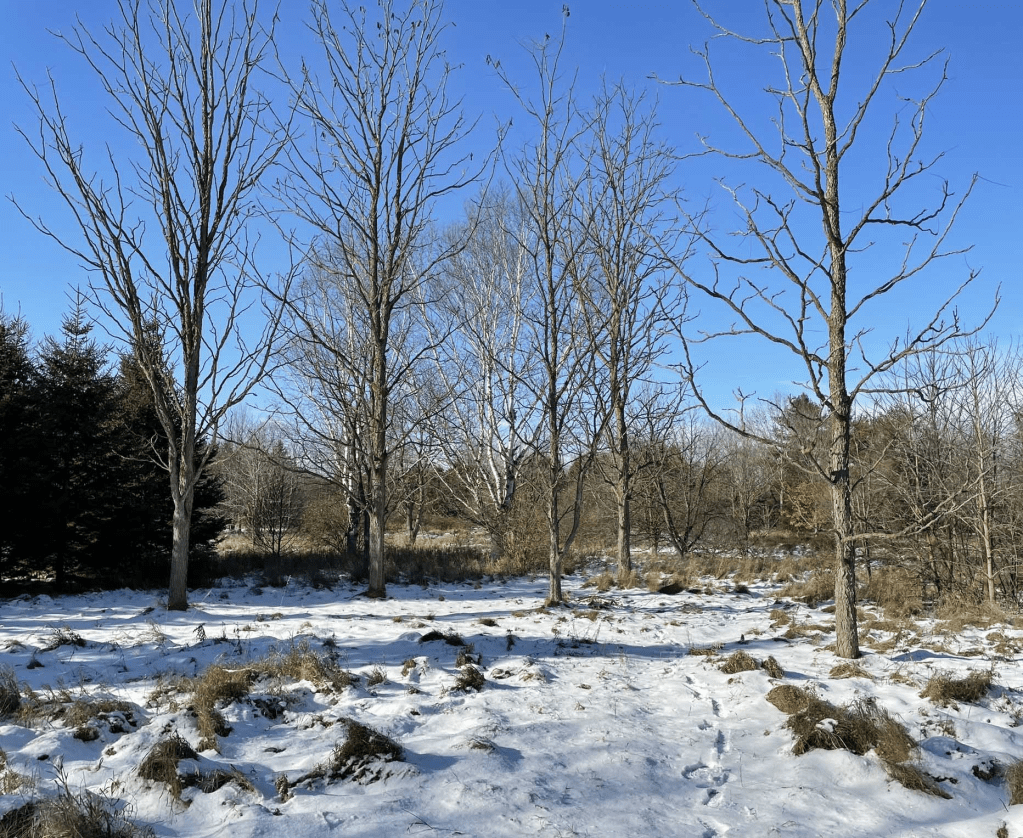

November 18: Guelph Lake Conservation Area

Long shadows, even mid-morning. Thirty-two days to the winter solstice. The woods are quiet, not even a chickadee calling. Leaves crunch underfoot.

Scattered along the old fencelines are apple trees, chance-grown from apple cores tossed by a farm worker or buried by a squirrel. The apples still hanging glow yellow in the bare branches, like Christmas ornaments; more lie beneath the trees. Little seems to have eaten them: no foxes, no coyotes? On the paths where I usually walk, evidence of fruit consumption is clear wherever there is coyote scat (and it’s always in the middle of the trail); not here, further away from the city. Why?

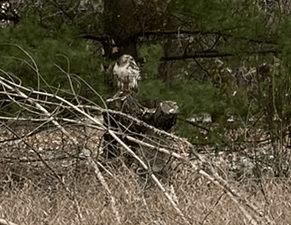

I come out of the wood into old fields. It’s 2 or 3 degrees C, and the breeze strong. A raptor catches my attention, soaring above the fields: a buteo, but not a red-tail. Three or four wingbeats, a short glide. Repeat, and repeat. The tail is barred, I note. The bird turns, and the low sun illuminates the rufous breast: a red-shouldered hawk, hunting voles, perhaps.

The path enters old deciduous forest, bordering an arm of the lake. Still silence here, except for the harsh cry of a red-bellied woodpecker, and another. The trail turns, drops down into cedars, and at a stream crossing there are, finally, chickadees, and the chip of juncos. The slowly-flowing stream is surrounded by green, even on this mid-November day.

There should be a counting rhyme for bluebirds. One on the bluebird box, two in the sky… They are landing and leaving, one by one, from on top of nest box, CW64: the one in which they were raised? Or simply a convenient stop on the way to the trees by the little pond? I count seven there, before they flash away, cerulean and russet, and I lose track of them.

November 19: University of Guelph Arboretum

Cold and bright this morning, and quiet out in the fields and woods. The birches that look so white when viewed without comparison are creamier than the clouds. Birds that echo the birches’ colours — chickadees, juncos — are calling from the shelter of cedars.

Squirrels are everywhere, both the black and gray morphs of the gray squirrel (and almost every combination of gray and black and fawn and white you can think of — there are black squirrels here with white stripes in their tails; squirrels with fawn bellies and almost-red pelages, even one with a tail ringed like a raccoon’s), and the smaller, fiercer red squirrel, mortal enemy of the larger grays. Every bustle in the hedgerow is a squirrel, unless it’s a chipmunk. And every few meters along almost every path are the gnawed-off shells of black walnuts, autumn bounty fattening the squirrels for winter survival.